The light and sound show at the Cellular Jail in Port Blair is a grand affair. It traces the history of colonialism, the Japanese occupation, the freedom struggle, and the atrocities committed against political prisoners. It’s an intense experience. But its grand finale feels less like a historical conclusion and more like a political statement, focusing on the glorification of a single hero central to the present regime and the mainstream consciousness. This selective focus is part of a larger, troubling pattern of rewriting history that extends from the name of the airport to the narratives we are told. In the process of elevating one story, others are deliberately silenced. What’s most troubling in this elaborate scheme of sights and colours is the complete erasure of the islands’ oldest story: the millennia-long history of its indigenous peoples.

If a book on the history of the islands were to be written, to paraphrase Pankaj Sekhsaria from memory, the entire history of British colonization would merit a page, while India’s administration would get a single paragraph. India, itself a victim of colonization, suffers from a cognitive dissonance—a denial of sorts—in not acknowledging its own role as a colonizer.

The post-independence era saw a period of fast-track colonization orchestrated by the Indian state. It all began with the plan of peopling the islands in the 1960s. Official government documents from the 1960s, as Sekhsaria points out, explicitly called them ‘Colonisation Schemes’. Indian colonization of the islands was a continuation of the cold chain as it were. It is hard to imagine the islands being part of Indian dominion had British not colonized it first. It was a gift from them in that sense. To encourage settlement, families from the mainland were offered a package that typically included 5 acres of paddy land, 5 acres of hilly land for cultivation, and a loan to procure cattle, in addition to the rights to timber for constructing a house.

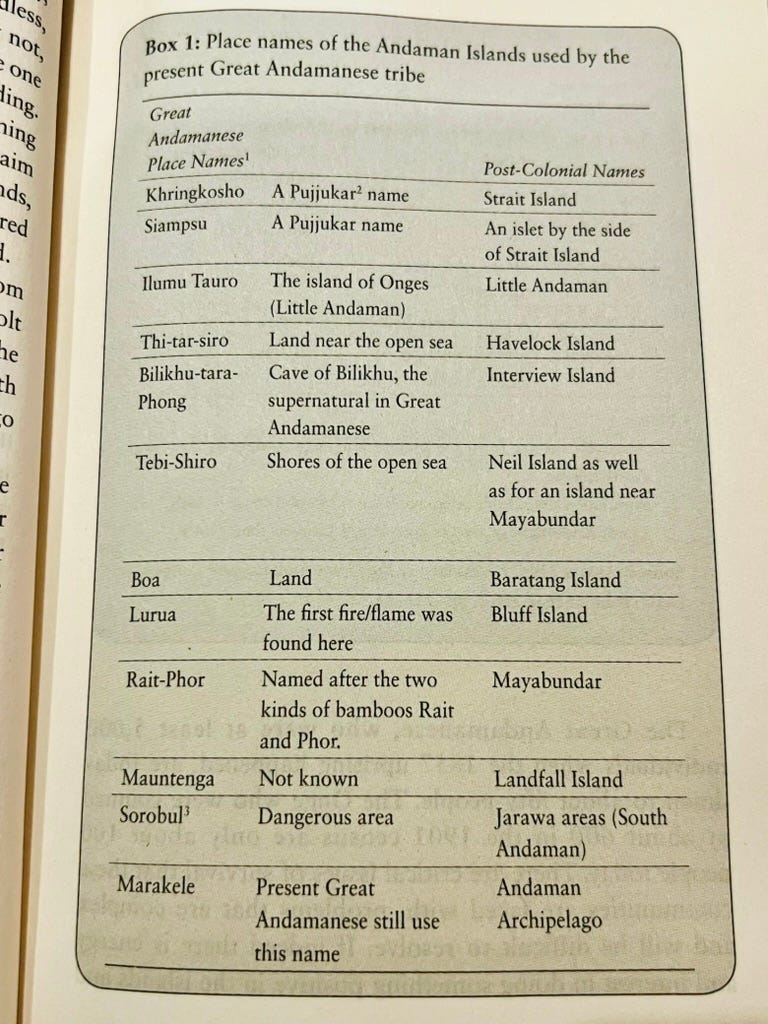

This process continues today through the act of renaming. Today Port Blair is Sri Vijaya Puram. Havelock Island is now officially Swaraj Dweep, Neil Island is Shaheed Dweep, and so on. We must, of course, erase relics of our colonial past. Mustn’t we? But what about our colonial present? Do we, for instance, stop to think what the original inhabitants think of these strange names? Did they, by chance, have their own names for these islands?

Of course, they did. Havelock Island, for instance, was Thi-tar-siro, ‘the land near the open sea’. Port Blair is Lao-tara Nyo to the Great Andamanese, which translates to the ‘house of evils or foreigners’. Just as well.

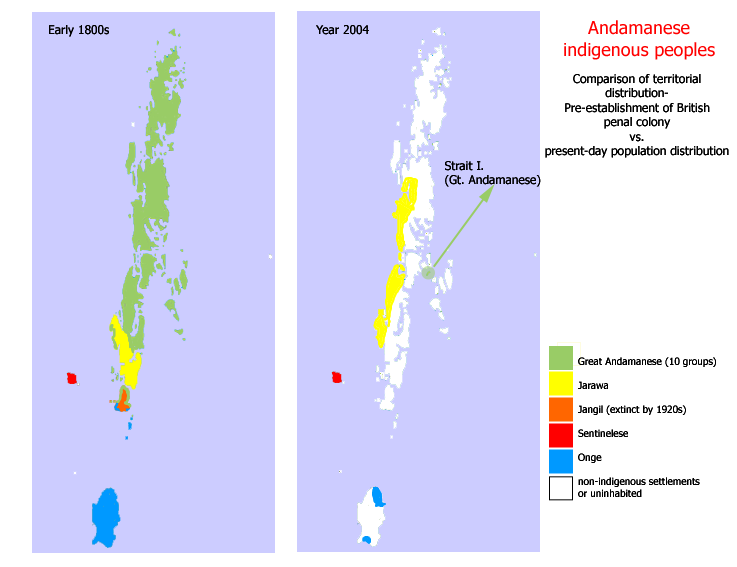

The Andaman and Nicobar Islands have been home to some of the first migrants out of Africa. These communities have a long history of living in isolation. In the 19th century, there were about 5,000 indigenous people—the Onge, Great Andamanese, Sentinelese, Jarawa, Nicobarese, and Shompen. Today, their numbers have dwindled to under 500, with some groups, like several of the Great Andamanese tribes, having vanished completely, and their languages, like Pujjukar, becoming extinct. Once spread throughout the archipelago, they are now restricted to a few reservations while mainland settlers occupy the rest of their homelands.

The story of tribal communities is the same the world over, whether in South America, Central India, or the Andamans. Contact with the ‘civilized’ world brings an onslaught of infectious diseases; poachers and illegal mafias introduce alcohol and tobacco, leading to addiction and sexual exploitation. Then the state enters the picture—seemingly to help—and introduces another form of dependency by providing rations and supplies. Yes, there is access to healthcare, but one wonders if that need was created in the first place by the forced contact imposed on them.

The Great Andaman Trunk Road, cutting through the Jarawa Tribal Reserve, is a testament to this imposition. It connects Port Blair with northern towns like Baratang, Mayabunder, and Diglipur. This road was constructed despite numerous protests from activist organizations and resistance from the Jarawa themselves. Despite multiple orders from the Supreme Court to limit or close the road, it continues to be operational. The construction of roads and bridges continues unabated.

The name ‘Jarawa’ is an interesting one. It’s not a word in the language spoken by the people we call Jarawa. In fact, it’s a word in the language of the Great Andamanese, a neighbouring group, that meant ‘stranger’ or ‘the other’. What do the ‘Jarawa’ call themselves? Or do they? There’s a word in their language—Aong—which connotes ‘we’ or ‘us’ or ‘our people’. Now, is that a word used as an identity for the tribe, or is it just that, a word? I ask because, do you really need to identify and differentiate yourself when you are living by yourself? Isn’t identity more often than not a manifestation of external forces? Doesn’t it get asserted under conflict?

But I digress.

We were told that the travel through the Jarawa reserve (yes, I am a hypocrite, no question) is a great experience—you will travel through dense and beautiful rainforests. We were also told that the vehicles move in a convoy and are not allowed to stop; if we happen to come across the Jarawa people, we just move on, or else they might shoot us with arrows—absolutely no contact.

I asked our driver as we were entering the reserve if we might see the Jarawa. (Yes, I did want to see what our earliest ancestors, the first humans of India still extant, might have looked like. I’m sorry.) “If you are lucky,” he remarked coolly. Well, yes. Recent estimates say they are all of 400-odd individuals. Could we really ‘spot’ them in these thick rainforests? As it turned out, by the end of our round trip, we had seen the whole range—so much so that I remarked, ‘Looks like we have met most of the clan.’ I was trying to make a joke of it, but I felt a strange sensation of guilt and shame. A sadness. What have we done here? Until a few decades ago, the Jarawa did fiercely resist intrusion. But since the late ‘90s, they have—especially the younger generation—been coming out. Today, they come to the road, wait there, and can be seen asking for food. Biscuit packets get thrown at kids who scramble for them and jump with joy.

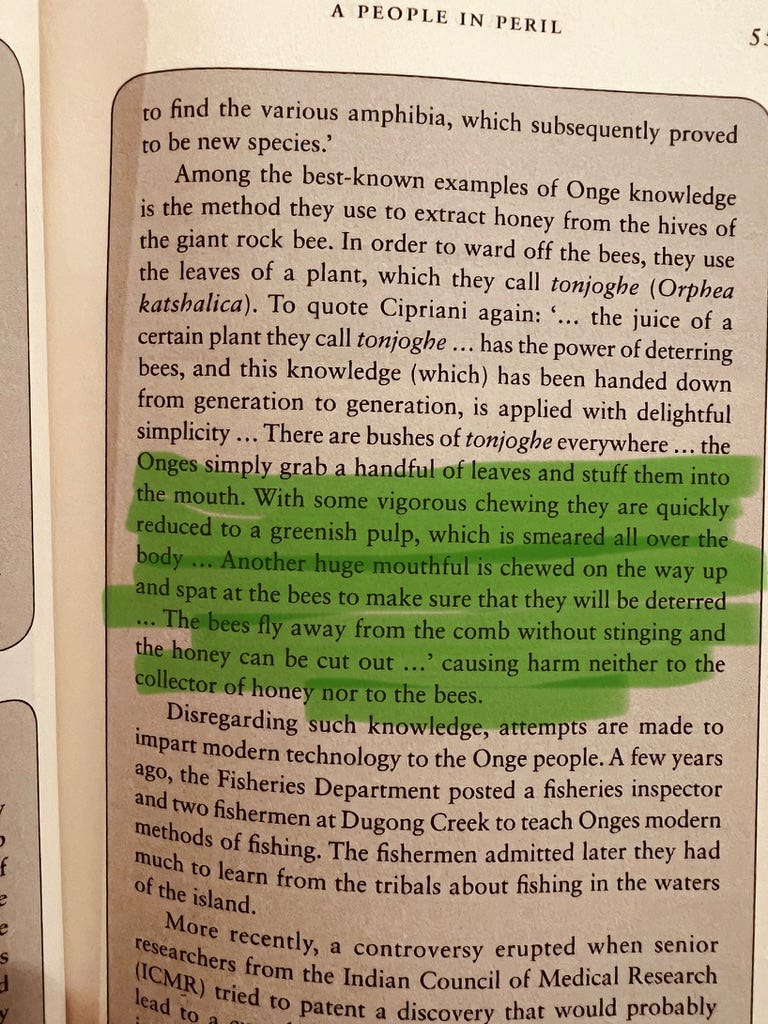

This stands in stark contrast to their profound indigenous knowledge. As described in Sekhsaria’s book, the Onge have a method of extracting honey from the hives of the giant rock bee. To ward off the bees, they don’t use fire or smoke but simply chew the leaves of a specific plant, tonjoghe, and smear the greenish pulp over their bodies. This repels the bees without harming them, allowing for a sustainable harvest. And famously, no one from these tribes died when the 2004 Tsunami hit; their acute environmental awareness and traditional warnings passed down through generations helped them move inland and to higher ground. What have we done to people who possess this kind of ecological wisdom?

Travelling, apart from being an enjoyable and relaxing experience, widens your horizons and gives you a better understanding of the world; but it also often leaves you with an acute sense of guilt. I suddenly remembered a brief note I had written a few years ago during a trip to Meghalaya. I remembered it as we were travelling on the bumpy and often non-existent road towards Diglipur. The feeling was familiar.

“Selfie Danger Zone and Landslide Ahead”

As we move gently along the curving roads carved on the East Khasi hills en route to Mawlynnong, there’s fog everywhere, slowing us down further. The fog set in quite early yesterday, much before sunset, as we headed out of Sohra (Cherrapunji). It’s a heavenly sight all around, with boundless valleys and streams flowing every which way one looks. From time to time, at a location where you get a panoramic, unobstructed view of the valley, one finds signage that says, “Selfie Danger Zone”. Pretty soon you start seeing the ugly profile of mined hills and mining trucks everywhere. Signage warning of potential “Landslide Ahead” follows soon after. Gorgeous valleys on one side with their selfie danger zones; butchered hills on the other with their landslide alerts.

I’m looking out the window of my cab trying to process all this. At first, man discovers these bounties of nature and settles down. Eventually, he invents something called tourism that helps people from distant lands partake in this joyous experience. People start flocking, needing more and bigger roads, homestays, resorts, restaurants, plastic, more everything—including more landslides. In a parallel thread, man invents photography, invents social media, puts tiny yet highly powerful cameras inside smartphones. Someone discovers the idea of a “selfie”. It spreads like a virus, eventually leading to selfie danger zones.

I know I’m rambling as I’m still trying to process all this. Selfies, social networks, tourism, landslides, plastic, and a myriad of other things are inexorably intertwined in my mind. I’m struggling to disentangle them so I can get some clarity. To see through the fog, as it were.

And the irony of I, a tourist, making these observations is not lost on me.

That same paradox was playing out on this Andaman road. The same dumper trucks, concrete mixers; dug up hills, reinforcement bars sticking out like sore thumbs. A thumbs up to development.

The government of India wants to increase tourism here tenfold. One can only imagine the consequences. What might that mean for the ecology of the place? What would that mean for the tribal communities?

Pankaj Sekhsaria has been fighting for the cause of the islands. He has been documenting this for decades, his writing often carrying the exhaustion of fighting a losing battle. You can sense a feeling of one step forward, two steps back in many of his essays.

As I read his book intermittently during my travel, I couldn’t help but think: had I read this before I embarked on that long journey on the Great Andaman Trunk Road, would I still have done it? I’m not completely sure. But that’s no longer the most important question.

Islands in Flux is a niche book. It’s extremely unlikely that I would have come across it or read it had I not travelled to the Andamans. But I’m glad I did. It’s an eye-opener. Not only in regard to these islands but in general to the destruction we are causing in the name of development and tourism.

The irony, I realize now, is not just that I was a tourist observing a tragedy; it’s that by participating, I was a part of it. Reading the book didn’t provide a solution, but it clarified the problem. It turns the question from a simple ‘Would I still have gone?’ to the far more unsettling ‘Now that I know, how do I carry this knowledge?’

Here it is population history..

Our Vanara Sainya?

Population histories of the Indigenous Adivasi and Sinhalese from Sri Lanka using whole genomes - ScienceDirect https://share.google/UxWBpj1KWvjprjfWK

Wonderfully written, as always..I was expecting this though... article has a beautiful flow, I liked it. Yes, I need to admit that Jared Diamond 's Guns, Germs and Steel did come up!

I've known about the archeoologio since the first ever episode in Doordarshan in a program called 'Surabhi'. Renuka Shane was a co-host.

It was wonderfully shot, and at the end of it all, both of them had the same somber, meloncholic tone, asking themselves - did we do it the right way? I've also read about a lady who first made contact with one tribe; she would float Coconut in water, learning that that was one action which the indigenous people somehow seemed to like...the story carried in the newspaper mentioned that she was the first human from our era to do this... decades have passed ..all the information camr to us in Newspapers, my grandfather would neatly cutout the article and file them - this was when I was in high school..

.it was a habit to check what he had cut out, even if he didn't like it. But once he sensed the curiosity in me, would discuss these issues on weekends - papers carried such articles in their Sunday special.

The incident you have mentioned, about the Tsunami, I did read the day it was published. While i pondered over it, i was in a time machine which took me back the days when we devoured Indrajal Comics... Phantom.

all the adages, in single sentences..Drums beat communication, what happens when Phantom walks, i can't recollect it now, but as chidren they were quoted when we played ! one news paper had a daily running clip, my brother was reading it in an animated way. My grandfather who was close by remarked, ' Are you aware, in all languages, a proverb is a sentence, and behind it is earthly wisdom and a STORY...isn't it amazing???

Phantom was not Andamanese... but the plight of the indigenous people across the world is the same. As kids reading these comics, we were so sensitive, but as we grow up, where does it all disappear???

This article brought back from memory, a speech I had the privilege to host at BMSri Prathishtana. GN Devy had tears in his eyes when he told how it affected him when they watched or got to know about the demise of the last woman who spoke that language. I have heared his speeches on YouTube, in each one of them, I see that man carrying a burden of pain, and may be even guilt, as you have explained. His book Mahabharata explains how the narrator Vyasa mentions about the Naimisharanya conclave of Rishis, where a group of bards, lead by SukaMuni narrate the story...At one point, he stops, and says, i know the story only till now, next lines , 'he knows'...a tribal. GN Devy, identified himself as a tribal!!! It is fascinating...

...Have you heard the speech Australian President gave to the parliament, apologising to the real. owners of the lands? Almost every one present teared up! I must look for the link!

In the US, we have read novels , watched movies...their plight explored with blinkers on our eyes.. again few are against affirmative actions, and they have to fight for it..Story repeats, addiction, sexual exploitation..

..When I was reading ' Mother Mary Comes to me ' Arundhati Roys were on my mind, at her best, sublime poetic prose about Jharkhand, Naxalitess, and state sponsered Salwa Judum...

..now we are hearing about all the word being started and ended, all because of the rare earth metals!!!

Where are we headed? Or, should we ask ourselves, was this the story of mankind from the very beginning? Reading thru several books on migration, and Ancient DNA Analysis, the impact they have had on the gene mutations causing rare disorders, I have pondered over this many times....

..And RSS just calls them Vanawasis..just so that doing so, helps build a wrong narrative of our of India story, I stop here, as I have come to the page you have shared first in this article, list of names renamed as sanskrit dweeps!

If Ravana is a tragic hero, was that a story of the last battle for survivors, fighting for their lands, to save themselves from the conqueror's from mainlands? Who knows for certain? This version of the story is only there in the regions where the land flora and fauna could have been similar in the south of India, some parts of Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Karnataka....strip all the layers, at the very bottom, I see only this..A Tragic Ravana portrayed by Nagachandra!!!

It is worth pondering over such issues from time to time, even though we can save ourselves that we are all victims of the times we are born into!

Enough of my rant. I stop here.

This is a deluge of memories, triggered by this poignant article, thanks for writing.

Aruna