This post is an English translation (with an updated conclusion section) of an essay originally written in Kannada by Sanket Patil. If you are interested in reading the original essay, you can find it here. An initial version of the Kannada essay was published in the September edition of Samajamukhi, a Kannada monthly magazine.

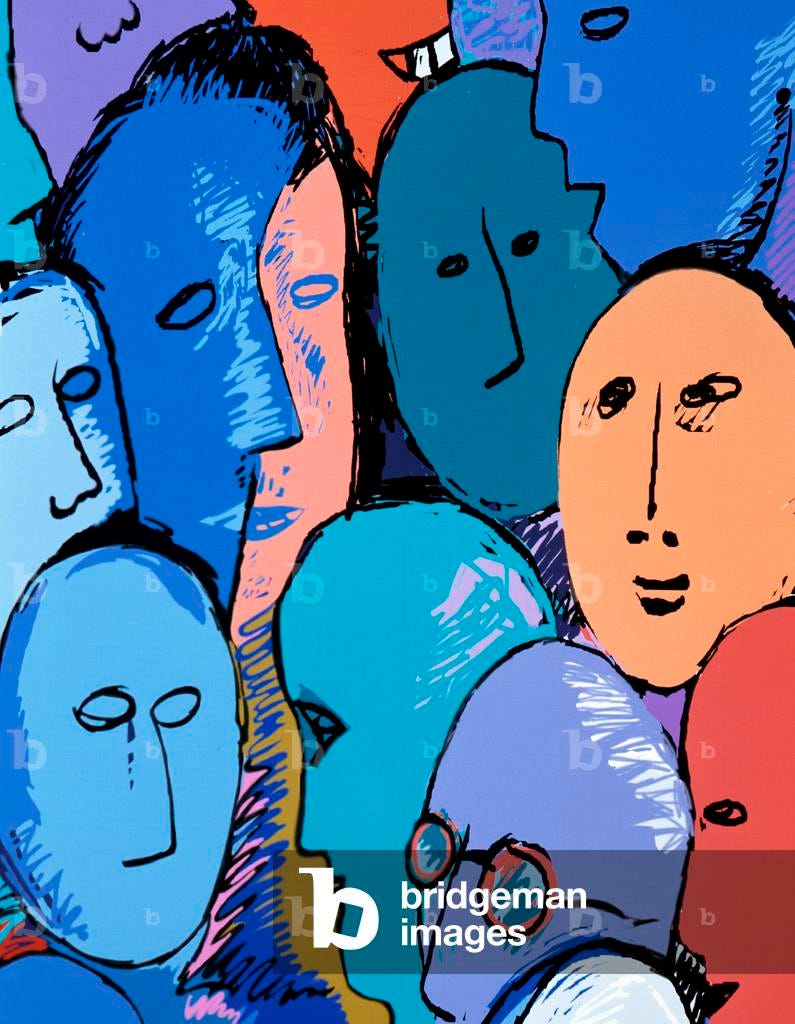

Picture a conversation about politics at home or among friends. What begins casually heats up fast. The situation pressures you to take a clear for-or-against position on some issue or policy; and on that basis, you’re instantly classified—as a supporter or opponent of Modi or Siddaramaiah (or Rahul Gandhi). The debate curdles into a quarrel.

That moment captures a snapshot of a larger malaise pervading our society. Our compulsion to oversimplify—to see only two opposing choices in everything—reveals a flaw in our reasoning. By ignoring complexity and papering over nuance, this habit blocks a fuller understanding and dictates how we respond to, and engage with, out immediate political, cultural, social, and even global conflicts.

Consider the farmers’ protests of 2020–21. What unfolded was not merely a policy dispute but a profound illustration of a societal schism. The establishment, with help from supporters and media, framed the movement as an illegitimate insurgency, branding farmers “Khalistanis” or “andolan-jivis” (professional agitators). The narrative hardened into patriots versus traitors. In response, protesters cast it as a grassroots struggle against corporate overreach. It became a collision of two irreconcilable worlds, with no space for accommodation. The eventual repeal was not a dialogue-driven consensus but a strategic political retreat, highlighting a failure of the argumentative process.

This is a local face of a global phenomenon. We are trapped in an argumentation crisis. This is not a mere decline in civility but a systemic consequence of a deeply rooted human cognitive preference for binaries. This innate tendency is now dangerously supercharged by political ideologies and social technologies.

There is no logical or ideological inconsistency in condemning the barbaric killings in Pahalgam as acts of Islamic terrorism while simultaneously condemning the regime’s warmongering that exploits such atrocities. One can recognize that war can sometimes become unavoidable and still worry about it and oppose it. It is possible to raise one’s voice against both Israel’s Zionist government and Hamas, while maintaining real empathy for ordinary people on both sides. Our “progressive” credentials are not diminished if we share Palestinian poems alongside the stories of Israelis dragged into a war they did not want, or if we condemn the oppression faced by countless women like Ahu Daryaei in Iran.

And yet, we pick a side and cling to it. We posture to impress our peers, to avoid their ire.

This tendency to force everything into our preferred ideological frames and binary-based thinking is growing in our discussions on society, economics, culture, and literature. For example: individual vs community, Dalit vs Savarna, oppressed vs oppressor, capitalism vs socialism. These lenses aren’t wrong; in many contexts, they are right and necessary. They’re just not sufficient. They can’t explain or resolve everything.

Look at food debates—the vegetarian vs. meat eater (popularly known as, “non-vegetarian”) squabbles. Or education—where a shallow understanding of “medium of instruction” keeps the Kannada vs English false dichotomy alive even today. It is not unnatural to support a right to food and simultaneously worry about the ecological impact of rising meat consumption; or to fight for equality and social justice while remaining open to the benefits of globalization and free markets. It is the mark of an educated mind, as the saying goes, to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it. We can hold apparently conflicting ideas in view and reconcile them. Seduced by simplistic narratives, we seem to be losing that ability.

This problem isn’t new. Gustave Le Bon, a French physician and polymath, understood this long before many others. His book, The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind, was a foundational work in social psychology, first published in 1895. Perhaps what he observed during the French Revolution—and the ‘Reign of Terror’ that led to the republic’s collapse and the rise of Napoleon—helped him crystallize his theory.

The essence of his work is captured in the line: “Alone, we think. In a crowd, we react.”

In a mob, he argued, individuality dissolves and reason yields to emotion. People are swept up by a collective mind—easily led, impulsive, and prone to extremes. Our primal nature takes over. We lose restraint, because responsibility now belongs not to any individual, but to the mob. A hypnotic frenzy spreads like a contagion. A “crowd” need not even share a physical space; we see lynch mobs and troll armies on social media all the time. (To be clear, the consequences are not always destructive; crowds can be mobilized for positive, heroic outcomes, though that is harder).

In any era, those who grasp a subject comprehensively and think deeply are few. But unlike in the past, information has become radically accessible in the last two decades. It is true that the internet and social networks are part of a global democratization process. It is just as true that they are part of a systematic weaponization process. (Whether platforms controlled by a few giant corporations are truly “democratic” is another question entirely).

In an age where algorithms select fragments of information—many of them half-baked and bias-confirming—to build us comfortable echo chambers; when a complex problem becomes fodder for a social media poll; when “activism” shrinks to endorsing and sharing online petitions; when an entire field of study can be distilled into a few ‘Shorts’—what we face is not just a political or cultural crisis. This is a generational epistemic crisis. We must ask the fundamental questions: Do we truly know what we claim to know? What is the source of that knowledge? By what methods did we acquire it?

To identify and correct the flaws in our thinking, we need to use the first principles, concepts, and tools from various fields like psychology, logic, economics, and game theory. They provide many useful mental models.

As mentioned, the symptom of binary classification that has now worsened is also a primitive survival strategy evolved for survival. When faced with a complex problem or danger, the brain evolved shortcuts and simple heuristics to process available information and make quick decisions. While these work effectively in many situations, in others they lead to our logical fallacies and prejudices, unconsciously shaping a black-and-white worldview.

Various cognitive biases work together to strengthen this kind of thinking.

One is confirmation bias: the tendency to search for, select, and remember only that information, argument, or data that strengthens our existing beliefs, while ignoring what contradicts them.

Another is negativity bias: giving far more weight to bad or unpleasant experiences than to good ones.

A third is the availability heuristic: making universal judgments based on events that easily come to mind (often linked to recency bias). For example, one recent incident of an assault on a migrant (or an act of oppression by a migrant) can instantly overshadow countless instances of long-term, peaceful coexistence.

Another such bias is the anchoring effect: an excessive reliance on the first piece of information offered (for example, the first set of leaked reports about the caste census) when making decisions.

There are dozens more such biases. Understanding them helps us identify the problems in our own thinking.

f cognitive biases and prejudices shape the structure of our limited thinking, Game Theory provides the terminology for it. Concepts like “zero-sum thinking,” “groupthink,” and “preference falsification” show how individual prejudices can aggregate to create collective paralysis.

A zero-sum game is a mathematical model of a situation (which could be a social relationship or an economic transaction) where the total sum of gains and losses of the participants remains zero. In such a case, one person’s gain comes at an equal loss for another. While this fits some situations, the real danger arises when this principle is unconsciously applied to most real-world problems. In most contexts, zero-sum thinking is a myth: a false perception that conflict is inherent in social relations and that one party’s victory is only possible through another’s defeat. This is deeply rooted in us.

This mindset denies the possibility of positive-sum outcomes—where greater value can be created for everyone when more people get opportunities. Instead of a mindset of cooperation and collaboration, it spreads bitterness, leading to unnecessary conflicts. This is glaringly visible in the debate on reservations. Even when there is strong evidence for the argument that true progress is possible only by including all sections of society and that this benefits everyone, the benefits received by lower classes are portrayed as opportunities directly snatched from the upper classes. We must instead realize that when more and more historically disadvantaged people get opportunities, it is possible, over time, to create more value for everyone. We must believe this can create a virtuous cycle. Along with this, we must also continue to think about how to increase the total quantum of opportunities, not just argue over dividing the current ones. Otherwise, we will only end up drowning in the for-and-against debate.

There is a direct and strong link between the socio-psychological concept of groupthink and zero-sum thinking. When a group’s desire for internal harmony and conformity becomes extreme, it begins to reject obvious truths and wisdom, becoming irrational and inert. When the world is perceived as a “us” vs “them” zero-sum war, group unity becomes the highest priority. There is no room for logic or factual assessment. The group turns inward, obsessed with its own purity and incapable of tolerating any dissent. This is accompanied by the demonization of opponents. Individuals belonging to the group will not express their doubts publicly, to avoid being “canceled” or ostracized.

The Turkish-American economist Timur Kuran, in a 1987 paper, put forward the concept of preference falsification. This refers to an individual hiding their true likes, dislikes, and opinions due to group or social pressure; or, performing a manufactured preference that is favorable to the group. For example, individuals who might privately hold a nuanced opinion—such as believing that the majority of Muslims in India are, like themselves, ordinary people with common aspirations who just want to live in peace—may suddenly sound like extremists on platforms like Twitter. Similarly, those who oppose a government policy stay silent, fearing the “anti-national” label. This silence of the majority, in turn, deepens political polarization.

Amartya Sen’s important work, The Argumentative Indian, begins with a reference to Krishna engaging in a detailed and lengthy philosophical discussion in the Bhagavad Gita. He then examines the questions raised by Gargi and Maitreyi and discusses the heterodoxy that has been embedded as a value in Indian civilizations since ancient times.

Even if dissent, pluralism, and heresy existed in our heritage, the reality is that they have been under assault for the last few decades. Not just dialogue, but the very possibility of it is diminishing, and we have become a “tongue-tied nation” (“ಮಾತು ಸೋತ ಭಾರತ”). Simplified perceptions and the zero-sum contest of easy binaries have taken hold.

To this, we must add a crucial counter-point. As Dr. B.R. Ambedkar argued, this celebrated “argumentative” tradition often co-existed with the oppressive hierarchy of caste—a rigid binary of “graded inequality”. The high-minded debate was largely the domain of a privileged elite, while the vast majority were systematically denied the right to even be heard.

This reframes our modern crisis completely. The challenge is not simply to revive Sen’s argumentative ideal, but to truly realize it for the first time by infusing it with Ambedkar’s non-negotiable demand for structural equality. The goal, then, is to build a genuinely pluralistic and inclusive public square, one that honors the supposed civilizational values that both Sen and Ambedkar, in their different ways, championed.

To overcome our “tongue-tied” state and achieve this requires a two-fold path:

Individual Cognitive Labor: We must actively resist our mental shortcuts, slow down, and seek out the dissenting perspectives we have been conditioned to ignore.

Collective and Institutional Change: We must demand and build a public square—from our social media algorithms to our public institutions—that rewards nuance and protects inclusivity, rather than profiting from outrage.

The goal is not to end disagreement, but to elevate its quality by ensuring its inclusivity—to dismantle the false binaries and finally build a public square where the complex, truthful spectrum of all voices can be heard.

You might also find this interesting …

The Unheeded Story of the Islands

The light and sound show at the Cellular Jail in Port Blair is a grand affair. It traces the history of colonialism, the Japanese occupation, the freedom struggle, and the atrocities committed against political prisoners. It’s an intense experience. But its grand finale feels less like a historical conclusion and more like a political statement, focusin…